|

TABLE CELL |

HELPER TEXT

|

|

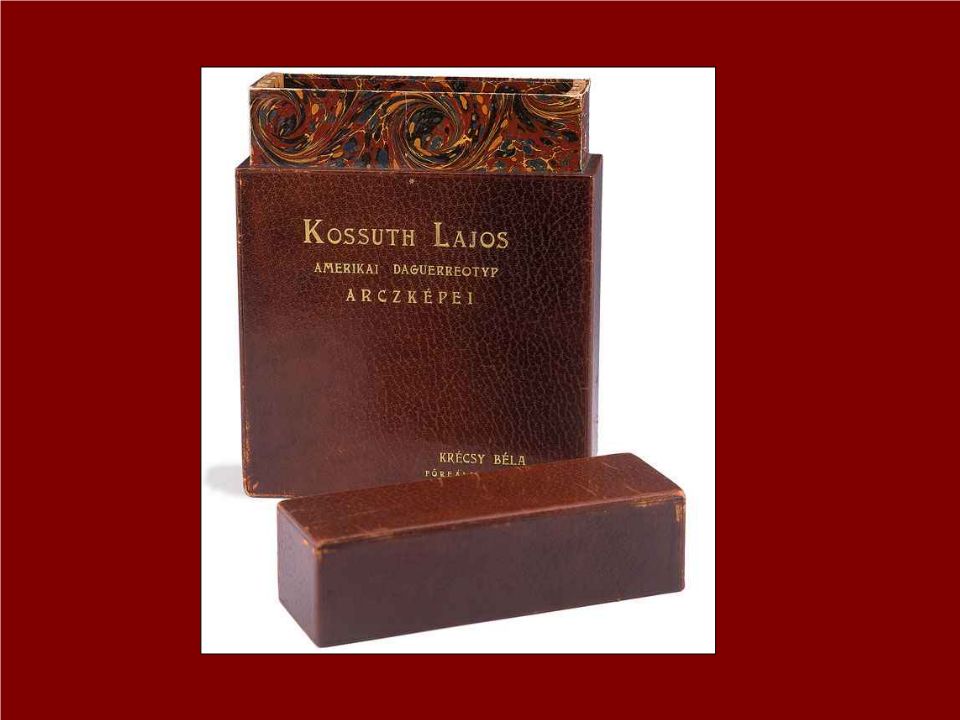

owner, inventory No. |

|

|

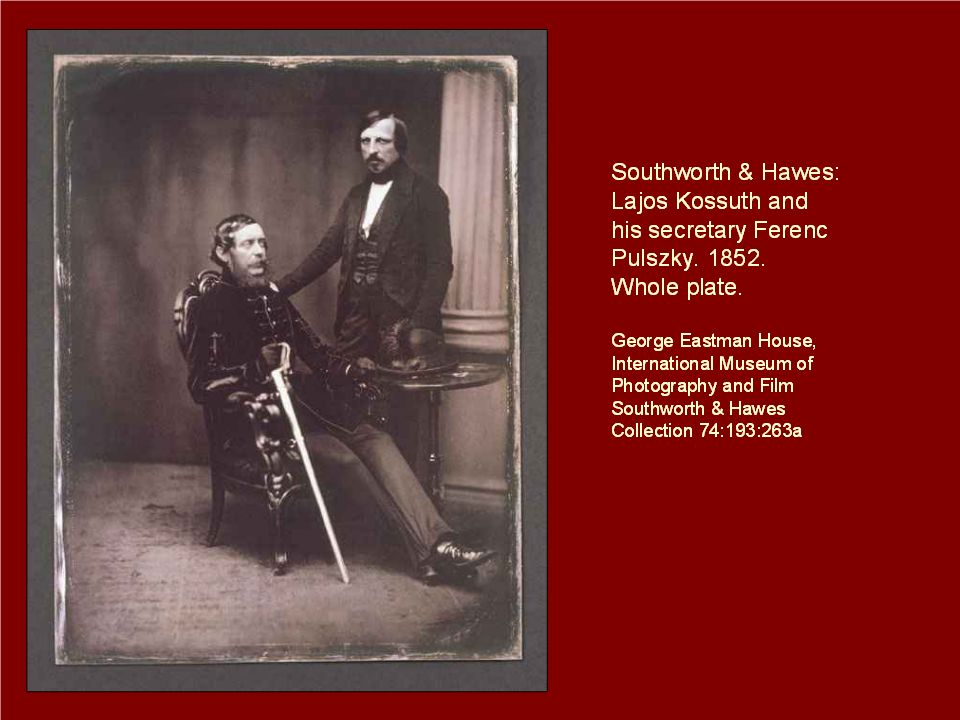

description of the picture, author |

man, woman, child, group,

copy, landscape photographer or atelier theme, or model name |

|

positon of the theme |

Left/right side of the original on the picture: reversed |

|

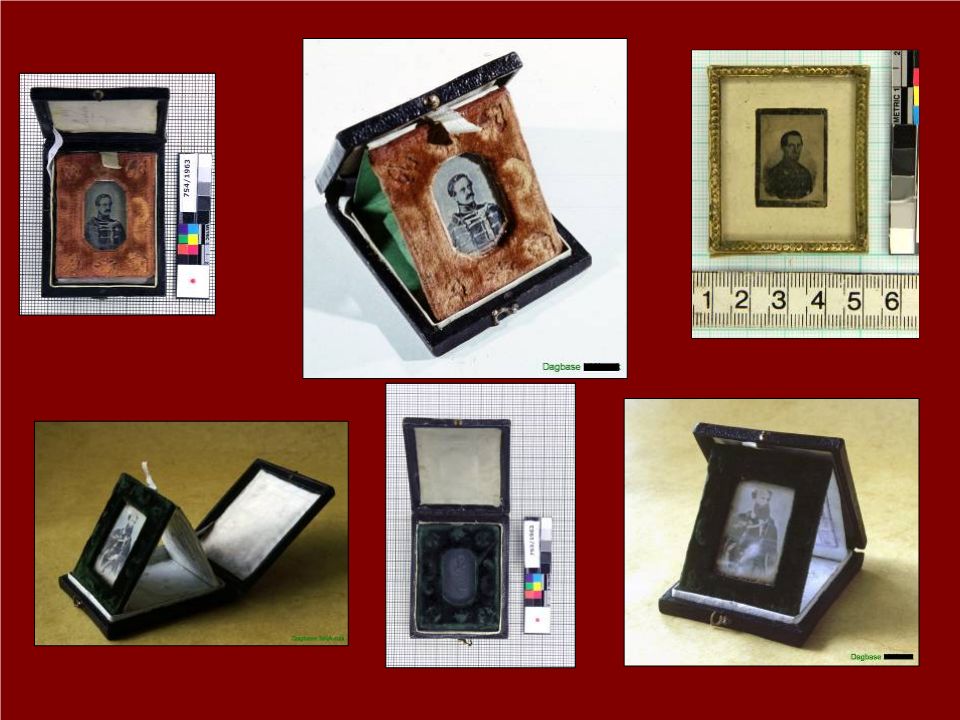

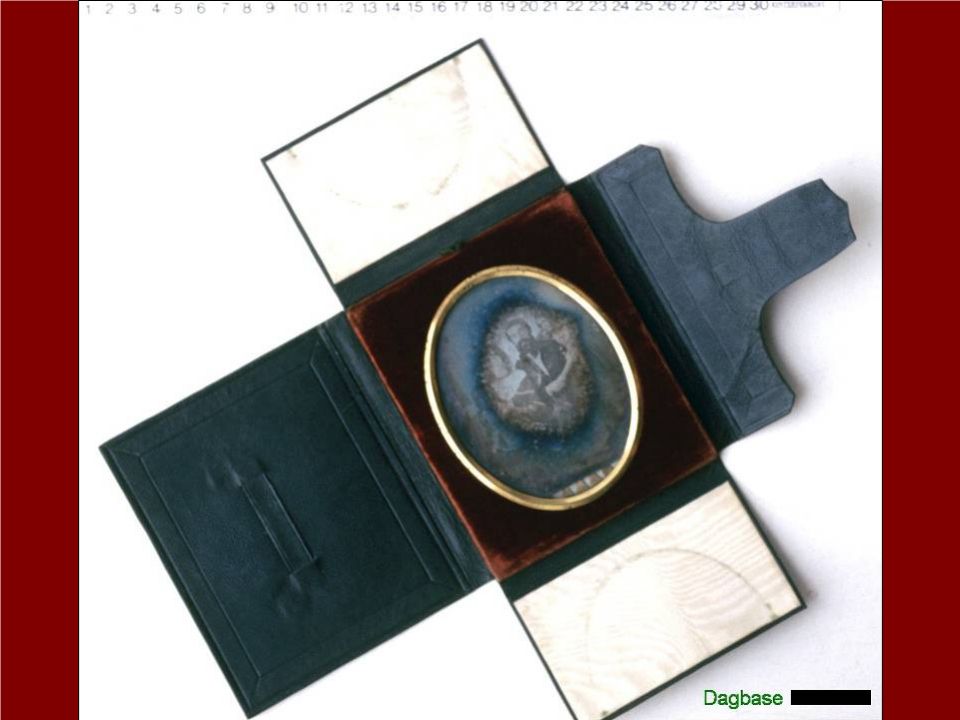

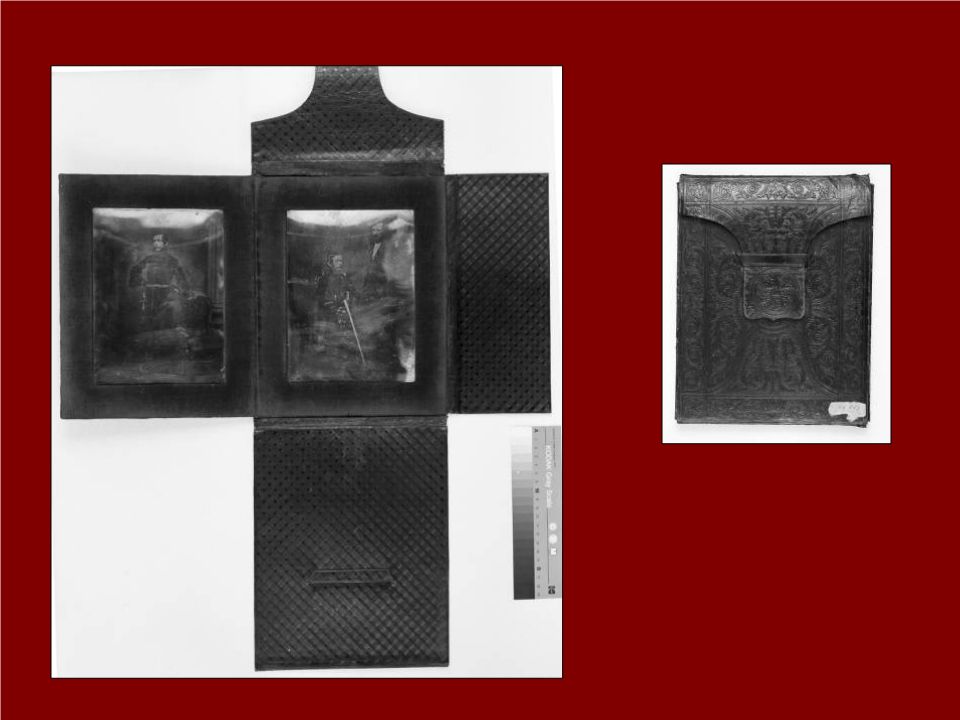

installation (case, frame, etc.) type, description |

Middle-European, West-European or French, Early or |

|

signature, other text(s) anywhere on the object place, description |

|

|

plate size and thickness (in mm-s)

|

.. mm x .. mm size name (eg: sixth plate) thickness: 0.5 mm |

|

hallmark, place, size, description |

M 40 30 20 |

|

description of the plate |

oxidation form: frame type

and average wide in mm, |

|

treatment |

Sealing, change deteriorating materials of the installation,

new glass plate (instead of original, under the original). mechanical

cleaning of plate, glass |

|

1. Record date 2. conservation 3. literature 4. notes |

1. 2. when, who 3. 4. |